Grappling On Foreign Soil

At mid-afternoon one day last month at the Azumazeki sumo stable, several snoring sumo wrestlers were spread out across the floor of an over-sized tatami-mat room. In a nearby corner, atop a television set, sat a miniature Christmas tree - a seemingly incongruous reminder of distant homes for the four foreigners who reside there.

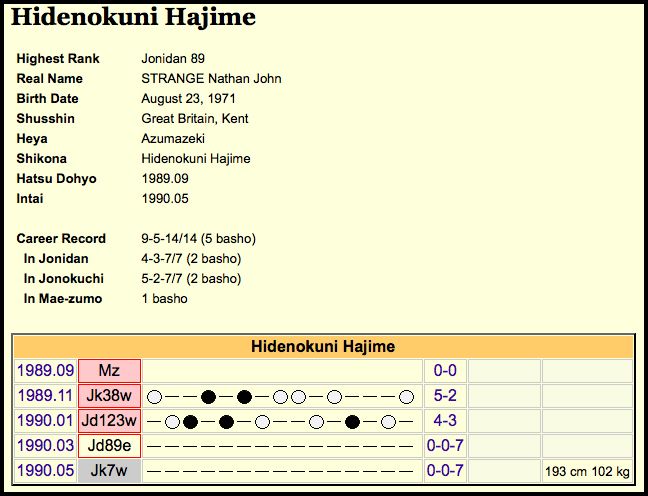

Downstairs, Nathan Strange stretched his limbs alongside the practice dohyo, his arms and legs well bruised from almost continual training. For Strange, who wrestles under the shikona of Hidenokuni, the tree had special meaning. This was the first Christmas abroad for the strapping 17-year-old Briton. “You have to leave home sometime,” he says, "so why not Japan?”

Why not indeed – especially if you want to become a sumo star? Strange is one of 19 foreigners currently competing, with varying degrees of success, in this most traditional of Japanese sports. In the last few years Japan has had more foreign sumotori than at any time in its history. Of the 70 foreigners who have tried their luck in the sport, nearly one-third have arrived since 1987, according to records kept by the Japan Sumo Association Museum. And for only the second time ever, one of them is the reigning champion.

Last November, Hawaiian-born Konishiki took the Emperor’s Cup at the grand sumo tournament in Kyushu. A repeat of the championship in the current tournament underway at Tokyo’s Ryogoku Kokugikan will put Konishiki, who at ozeki is already the highest ranked non-Japanese ever, in line for promotion to the pinnacle of the sport, the yokozuna rank. Regardless of how he fares, his accomplishments have already given a big boost to the aspirations of the foreign contingent.

From the time they strap on their first mawashi, foreign wrestlers, mostly from Hawaii and Taiwan but some from as far away as Argentina, receive no special considerations such as those afforded American baseball players drawn to Japan by high salaries. Like their Japanese counterparts, they start at the bottom of a strict ranking system, subjected to feudal hardships beyond the usual cultural problems that come with living in a different country. Even some of the more successful ones have quit, beaten not by opponents in the ring, but by an inability to adapt to the regimented lifestyle demanded of a sumo wrestler. “The biggest problem (for foreigners) is trying to accept the sumo way of life,” says Hawaiian-born stablemaster Azumazeki, whose real name is Jesse Kuhualua and who rose to fame as Takamiyama when he became the first non-Japanese born champion, winning the Nagoya basho in 1972. “It’s hard to accept the work; how we eat, get up in the morning, bust your ass, cook your own meals, KP duty, people picking on you.”

That, says Azumazeki, requires patience – lots of it. “If you can do that and be patient and work hard,” he says, “I think you can become a good sumo wrestler.” The reason is that all newcomers are given the most menial tasks at the stables. They must wash the clothes, cook the food – all just for room and board. It becomes difficult for the foreigner arriving here with illusions of grandeur, to endure such demeaning tasks while trying to work his way up the rankings – where the accompanying perks make the sacrifices a bit easier to bear.

One of those paying the price is Chad Rowan, one of the four foreigners in the Azumazeki stable. (Ed.'s note; Rowan went on to become yokozuna Akebono). Rowan, a former all-state high school basketball player in Hawaii – and at 204 centimeters sumo’s tallest wrestler – is ranked No. 2 in the makushita division. Winning a majority of his seven bouts in the 15-day tournament should ensure his promotion to the Juryo rank, which will entitle him to a monthly salary – plus a highly valued private room at the stable. Such determination doesn’t necessarily run in families, however. Rowan’s younger brother George got himself expelled from the Azumazeki stable after only a few months for not abiding by the rules.

Even Strange, who came to Japan with an abiding fascination with the country, found the cultural transition difficult. He considered quitting before competing in his first tournament. Even now, despite some initial success – he posted a 3-1 mark in maezumo and an impressive 5-2 record in the lowest jonokuchi division of the November tournament – he admits, “I’m having a rough time.” One problem for Strange, the first European sumotori, has been the food. The rich stew-like chanko that forms the bulk of a sumotori’s diet was apparently too much for the Londoner. Instead of gaining weight, he lost 22 kilograms in the first two months. “I can eat a bit more now,” says Strange, who weighed 5,670 grams at birth and now tips the scales at 107 kilograms. “I’ve only started to put (the weight) back on. “He’s going through a lot of hell,” Azumazeki acknowledges. “I know that, but he’s got to learn to accept these things, these problems.”

One man who found that raw talent alone was no match for the demanding sumo lifestyle was John Tenta, Canada’s first and only sumotori. A former world junior freestyle wrestling champion, Kototenzan did not lose a match in the six months he competed, but then quit just prior to the May tournament in 1986. Impatient to get out of the unsalaried lower ranks, the bull-like Tenta later joined Japan’s pro wrestling circuit. “The only problem with him was the dollar signs in his mind,” says Azumazeki. “He could have become a good strong rikishi; he just couldn’t accept the life of a sumo wrestler.”

Another former rikishi, the muscular Kiriful Saba, who rose to maegashira 2 as Nankairyu, does not hesitate to admit that the sumo way of life, and what he claims as its overly restrictive rules, led to his sudden departure in the final days of last November’s tournament. “There are too many rules in sumo,” Konishiki’s former stablemate recently told a Japanese weekly from his home in Western Samoa. “After a match, you go back to the stable and all they do is order you around like a child.”

In the same way that foreigners are not always ready for sumo, however, sumo sometimes seems unready for foreigners. When Konishiki first burst upon the sumo scene several years ago with a series of impressive tournaments that appeared to put him on track to gain the vaunted yokozuna rank, there were grumblings about foreigners becoming too powerful in Japan’s purest sport. Now, ironically, Konishiki’s dogged comeback from knee injury, his recent championship and the generally favorable reception he received may prove to be a turning point in acceptance of foreigners in sumo. Almost certainly, it will encourage even more foreigners to enter the hallowed ring.

- Ken Marantz: Jan 18th 1990